The Oceanic Steam Navigation Company or White Star Line of Boston Packets, more commonly known as just White Star Line, was a prominent British shipping company, today most famous for their ground-breaking vessel Oceanic of 1870, their ill-fated vessel RMS Titanic, and the World War I loss of Titanic‘s sister ship Britannic.

The Oceanic Steam Navigation Company or White Star Line of Boston Packets, more commonly known as just White Star Line, was a prominent British shipping company, today most famous for their ground-breaking vessel Oceanic of 1870, their ill-fated vessel RMS Titanic, and the World War I loss of Titanic‘s sister ship Britannic.

In 1934 White Star merged with its chief rival, Cunard Line, which operated as Cunard-White Star Line until 1950. Cunard Line then operated as a separate entity until 2005 and is now part of Carnival Corporation & plc. As a lasting reminder of the White Star Line, modern Cunard ships use the term White Star Service to describe the level of customer care expected of the company.

Early history

The first company bearing the name White Star Line was founded in Liverpool, England, by John Pilkington and Henry Wilson in 1845. It focused on the UK–Australia trade, which increased following the discovery of gold in Australia. The fleet initially consisted of the chartered sailing ships RMS Tayleur, Blue Jacket, White Star, Red Jacket, Ellen, Ben Nevis, Emma, Mermaid and Iowa. Tayleur, the largest ship of its day, wrecked on its maiden voyage to Australia at Lambay Island, near Ireland, a disaster that haunted the company for years.

The first company bearing the name White Star Line was founded in Liverpool, England, by John Pilkington and Henry Wilson in 1845. It focused on the UK–Australia trade, which increased following the discovery of gold in Australia. The fleet initially consisted of the chartered sailing ships RMS Tayleur, Blue Jacket, White Star, Red Jacket, Ellen, Ben Nevis, Emma, Mermaid and Iowa. Tayleur, the largest ship of its day, wrecked on its maiden voyage to Australia at Lambay Island, near Ireland, a disaster that haunted the company for years.

In 1863, the company acquired its first steamship, the Royal Standard.

The original White Star Line merged with two other small lines, The Black Ball Line and The Eagle Line, to form a conglomerate, the Liverpool, Melbourne and Oriental Steam Navigation Company Limited. This did not prosper and White Star broke away. White Star concentrated on Liverpool to New York services. Heavy investment in new ships was financed by borrowing, but the company’s bank, the Royal Bank of Liverpool, failed in October 1867. White Star was left with an incredible debt of £527,000, (£40,715,117 as of 2014), and was forced into bankruptcy.

The Oceanic Steam Navigation Company

On 18 January 1868, Thomas Ismay, a director of the National Line, purchased the house flag, trade name and goodwill of the bankrupt company for £1,000, (£78,505 as of 2014), with the intention of operating large ships on the North Atlantic service. Ismay established the company’s headquarters at Albion House, Liverpool.

Ismay was approached by Gustav Christian Schwabe, a prominent Liverpool merchant, and his nephew, shipbuilder Gustav Wilhelm Wolff, during a game of billiards. Schwabe offered to finance the new line if Ismay had his ships built by Wolff’s company, Harland and Wolff. Ismay agreed, and a partnership with Harland and Wolff was established. The shipbuilders received their first orders on 30 July 1869. The agreement was that Harland and Wolff would build the ships at cost plus a fixed percentage and would not build any vessels for the White Star’s rivals. In 1870 William Imrie joined the managing company. As the first ship was being commissioned, Ismay formed the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company to operate the steamers under construction.

Ismay was approached by Gustav Christian Schwabe, a prominent Liverpool merchant, and his nephew, shipbuilder Gustav Wilhelm Wolff, during a game of billiards. Schwabe offered to finance the new line if Ismay had his ships built by Wolff’s company, Harland and Wolff. Ismay agreed, and a partnership with Harland and Wolff was established. The shipbuilders received their first orders on 30 July 1869. The agreement was that Harland and Wolff would build the ships at cost plus a fixed percentage and would not build any vessels for the White Star’s rivals. In 1870 William Imrie joined the managing company. As the first ship was being commissioned, Ismay formed the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company to operate the steamers under construction.

White Star began with six ships of the Oceanic class: Oceanic (I), Atlantic, Baltic, and Republic, followed by the slightly larger Celtic and Adriatic. White Star began operating again in 1871 between New York and Liverpool (with a call at Queenstown).

It has long been customary for many shipping lines to have a common theme for the names of their ships. White Star gave their ships names ending in -ic, such as Titanic. The line also adopted a buff-coloured funnel with a black top as a distinguishing feature for their ships, as well as a distinctive house flag, a red broad pennant with two tails, bearing a white five-pointed star.

It has long been customary for many shipping lines to have a common theme for the names of their ships. White Star gave their ships names ending in -ic, such as Titanic. The line also adopted a buff-coloured funnel with a black top as a distinguishing feature for their ships, as well as a distinctive house flag, a red broad pennant with two tails, bearing a white five-pointed star.

The first substantial loss for the company came only four years after its founding, occurring in 1873 with the sinking of the SSAtlantic and the loss of 535 lives near Halifax, Nova Scotia. While en route to New York from Liverpool amidst a vicious storm, the Atlantic attempted to make port at Halifax when a concern arose that the ship would run out of coal before reaching New York.  However, when attempting to enter Halifax, she ran aground on the rocks and sank in shallow waters. Despite being so close to shore, a majority of the victims of the disaster drowned. The crew were blamed for serious navigational errors by the Canadian Inquiry, although a British Board of Trade investigation cleared the company of all extreme wrongdoing.

However, when attempting to enter Halifax, she ran aground on the rocks and sank in shallow waters. Despite being so close to shore, a majority of the victims of the disaster drowned. The crew were blamed for serious navigational errors by the Canadian Inquiry, although a British Board of Trade investigation cleared the company of all extreme wrongdoing.

During the late nineteenth century, White Star operated many famous ships, such as Britannic (I), Germanic, Teutonic, and Majestic (I). Several of these ships took the Blue Riband, awarded to the fastest ship to make the Atlantic crossing.

In 1899 Thomas Ismay commissioned one of the most beautiful steam ships constructed during the nineteenth century, the Oceanic (II). She was the first ship to exceed the Great Eastern in length (although not tonnage). The building of this ship marked White Star Line’s departure from competition in speed with its rivals. Thereafter White Star concentrated on comfort and economy of operation instead.

In the late nineteenth century, shipbuilders had discovered that when speed through water increased above about 20 knots (23 mph; 37 km/h), the required additional engine power increased in logarithmic proportion: that is, each additional increment of speed required a larger increase in engine power and fuel consumption. With the coal-fired reciprocating steam engines of the time, exceeding about 24 knots (28 mph; 44 km/h) required very high power and fuel consumption.

For this reason, the White Star Line committed to comfort and reliability rather than to speed. For example, White Star’s Celtic cruised at 16 knots (18 mph; 30 km/h) with 14,000 horsepower, while Cunard’s Mauretania made 24 knots (28 mph; 44 km/h) with 68,000 horsepower.

For this reason, the White Star Line committed to comfort and reliability rather than to speed. For example, White Star’s Celtic cruised at 16 knots (18 mph; 30 km/h) with 14,000 horsepower, while Cunard’s Mauretania made 24 knots (28 mph; 44 km/h) with 68,000 horsepower.

Between 1901 and 1907, White Star brought "The Big Four" (all around 24,000 tons) into service: Celtic, Cedric, Baltic, and Adriatic. These ships carried massive numbers of passengers: 400 passengers in First and Second Class, and over 2,000 in Third Class. In addition, they had extremely large cargo capacities, up to 17,000 tons of general cargo.

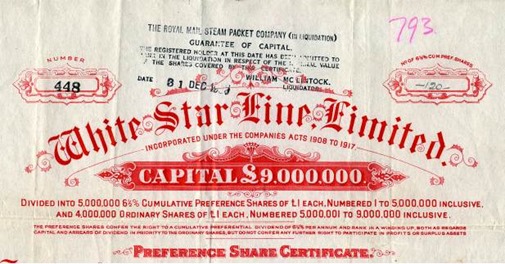

In 1902 White Star Line was absorbed into the International Mercantile Marine Co. (IMM), a large American shipping conglomerate. Bruce Ismay ceded control to IMM in the face of intense pressure from shareholders and J. P. Morgan, who threatened a rate war. IMM was dissolved in 1932.

In 1933 White Star and Cunard were both in serious financial difficulties because of the Great Depression, falling passenger numbers and the advanced age of their fleets. Work was halted on Cunard’s new giant, Hull 534 (later the Queen Mary) in 1931 to save money. In 1933 the British government agreed to provide assistance to the two competitors on the condition that they merge their North Atlantic operations. The agreement was completed on 30 December 1933.

Cunard merger

The merger took place on 10 May 1934, creating Cunard-White Star Limited. White Star contributed ten ships to the new company while Cunard contributed 15 ships. Because of this, and since Hull 534 was Cunard’s ship, 62% of the company was owned by Cunard’s shareholders and 38% of the company was owned for the benefit of White Star’s creditors. White Star’s Australia and New Zealand services were not involved in the merger, but were separately disposed of to Shaw, Savill & Albion later in 1934. A year after this merger, Olympic, the last of her class, was removed from service. She was scrapped in 1937.

The merger took place on 10 May 1934, creating Cunard-White Star Limited. White Star contributed ten ships to the new company while Cunard contributed 15 ships. Because of this, and since Hull 534 was Cunard’s ship, 62% of the company was owned by Cunard’s shareholders and 38% of the company was owned for the benefit of White Star’s creditors. White Star’s Australia and New Zealand services were not involved in the merger, but were separately disposed of to Shaw, Savill & Albion later in 1934. A year after this merger, Olympic, the last of her class, was removed from service. She was scrapped in 1937.

In 1947 Cunard acquired the 38% of Cunard White Star they did not already own, and on 31 December 1949 they acquired Cunard White Star’s assets and operations, and reverted to using the name "Cunard" on January 1, 1950. From the time of the 1934 merger, the house flags of both lines had been flown on all their ships, with each ship flying the flag of its original owner above the other, but from 1950, even Georgic and Britannic, the last surviving White Star liners, flew the Cunard house flag above the White Star burgee until they were each withdrawn from service, in 1956 and 1961 respectively. Just as the retiring of Cunard Line’s RMS Aquitania in 1949 marked the end of an era, so the retirement of the Britannic and therefore the last vestiges of the famous White Star Line was similarly noted world-wide. All other ships flew the Cunard flag over the White Star flag until 1968.

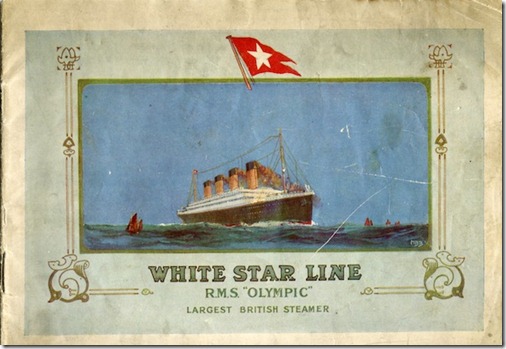

The Ship on the poster

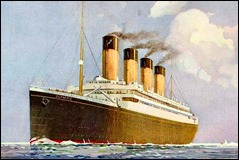

RMS Olympic was a transatlantic ocean liner, the lead ship of the White Star Line‘s trio of Olympic-class liners. Unlike her younger sister ships, the Olympic enjoyed a long and illustrious career, spanning 24 years from 1911 to 1935. This included service as a troopship during World War I, which gained her the nickname "Old Reliable". Olympic returned to civilian service after the war and served successfully as an ocean liner throughout the 1920s and into the first half of the 1930s, although increased competition, and the slump in trade during the Great Depression after 1930, made her operation increasingly unprofitable.

She was the largest ocean liner in the world for two periods during 1911–13, interrupted only by the brief tenure of the slightly larger Titanic (which had the same dimensions but higher gross tonnage due to revised interior configurations), and then outsized by the SS Imperator. Olympic also retained the title of the largest British-built liner until the RMS Queen Mary was launched in 1934, interrupted only by the short careers of her slightly larger sister ships.

By contrast with Olympic, the other ships in the class, Titanic and Britannic, did not have long service lives. On the night of 14/15 April 1912, Titanic collided with an iceberg in the North Atlantic and sank, claiming 1,500 lives; Britannic struck a mine and sank in the Kea Channel in the Mediterranean on 21 November 1916, killing 30 people.

Features

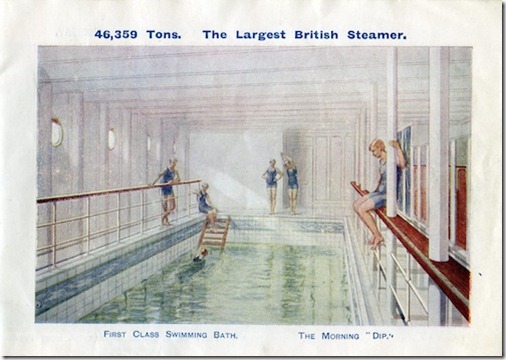

The Olympic was designed as a luxury ship; her passenger facilities, fittings, deck plans and technical facilities were largely identical to those of her more famous sister Titanic, although with some small variations. The first-class passengers enjoyed luxurious cabins, and some were equipped with private bathrooms. First-class passengers could have meals in the ship’s large and luxurious dining room or in the more intimate A La Carte Restaurant. There was a lavish Grand Staircase, built only for the Olympic-class ships, along with three

The Olympic was designed as a luxury ship; her passenger facilities, fittings, deck plans and technical facilities were largely identical to those of her more famous sister Titanic, although with some small variations. The first-class passengers enjoyed luxurious cabins, and some were equipped with private bathrooms. First-class passengers could have meals in the ship’s large and luxurious dining room or in the more intimate A La Carte Restaurant. There was a lavish Grand Staircase, built only for the Olympic-class ships, along with three  elevators that ran behind the staircase down to E deck, a Georgian-style smoking room, a Veranda Café decorated with palm trees, a swimming pool, Turkish bath, gymnasium, and several other places for meals and entertainment.

elevators that ran behind the staircase down to E deck, a Georgian-style smoking room, a Veranda Café decorated with palm trees, a swimming pool, Turkish bath, gymnasium, and several other places for meals and entertainment.

The second-class facilities included a smoking room, a library, a spacious dining room, and an elevator.

Finally, the third-class passengers enjoyed reasonable accommodation compared to other ships, if not up to the second and first classes. Instead of  large dormitories offered by most ships of the time, the third-class passengers of the Olympic travelled in cabins containing two to ten bunks. Facilities for the third class included a smoking room, a common area, and a dining room.

large dormitories offered by most ships of the time, the third-class passengers of the Olympic travelled in cabins containing two to ten bunks. Facilities for the third class included a smoking room, a common area, and a dining room.

Olympic had a cleaner, sleeker look than other ships of the day: rather than fitting her with bulky exterior air vents, Harland and Wolff used smaller air vents with electric fans, with a "dummy" fourth funnel used for additional ventilation.  For the power plant Harland and Wolff employed a combination of reciprocating engines with a centre low-pressure turbine, as opposed to the steam turbines used on Cunard’s Lusitania and Mauretania. White Star had successfully tested this engine set up on an earlier liner SS Laurentic, where it was found to be more economical than expansion engines or turbines alone. Olympic consumed 650 tons of coal per 24 hours with an average speed of 21.7 knots on her maiden voyage, compared to 1000 tons of coal per 24 hours for both the Lusitania and Mauretania.

For the power plant Harland and Wolff employed a combination of reciprocating engines with a centre low-pressure turbine, as opposed to the steam turbines used on Cunard’s Lusitania and Mauretania. White Star had successfully tested this engine set up on an earlier liner SS Laurentic, where it was found to be more economical than expansion engines or turbines alone. Olympic consumed 650 tons of coal per 24 hours with an average speed of 21.7 knots on her maiden voyage, compared to 1000 tons of coal per 24 hours for both the Lusitania and Mauretania.

Although Olympic and Titanic were nearly identical, and were based on the same design, a few alterations were made to Titanic (and later on Britannic) based on experience gained from Olympic‘s first year in service. The most noticeable of these was that the forward half of the Titanic‘s A Deck promenade was enclosed by a steel screen with sliding windows, to provide additional shelter, whereas the Olympic‘s promenade deck remained open along its whole length. Also the promenades on the Titanic‘s B Deck were reduced in size, and the space used for additional cabins and public rooms, including two luxury suites with private promenades. A number of other variations existed between the two ships layouts and fittings. These differences meant that Titanic had a slightly higher gross tonnage of 46,328 tons, compared to Olympic‘s 45,324 tons.

Although Olympic and Titanic were nearly identical, and were based on the same design, a few alterations were made to Titanic (and later on Britannic) based on experience gained from Olympic‘s first year in service. The most noticeable of these was that the forward half of the Titanic‘s A Deck promenade was enclosed by a steel screen with sliding windows, to provide additional shelter, whereas the Olympic‘s promenade deck remained open along its whole length. Also the promenades on the Titanic‘s B Deck were reduced in size, and the space used for additional cabins and public rooms, including two luxury suites with private promenades. A number of other variations existed between the two ships layouts and fittings. These differences meant that Titanic had a slightly higher gross tonnage of 46,328 tons, compared to Olympic‘s 45,324 tons.

Text from Wikipedia