Margaretha Geertruida "M’greet" Zelle MacLeod (7 August 1876 – 15 October 1917), better known by the stage name Mata Hari, was a Dutch exotic dancer and courtesan who was convicted of being a spy and executed by firing squad in France under charges of espionage for Germany during World War I.

Margaretha Geertruida "M’greet" Zelle MacLeod (7 August 1876 – 15 October 1917), better known by the stage name Mata Hari, was a Dutch exotic dancer and courtesan who was convicted of being a spy and executed by firing squad in France under charges of espionage for Germany during World War I.

Early life

Margaretha Geertruida Zelle was born in Leeuwarden, Netherlands. Her birthhouse, at Kelders 33, survived a big fire that ruined the three houses next to it on 19 October 2013. She was the eldest of four children of Adam Zelle (2 October 1840 – 13 March 1910) and his first wife Antje van der Meulen (21 April 1842 – 9 May 1891). She had three brothers. Her father owned a hat shop, made successful investments in the oil industry, and became affluent enough to give Margaretha a lavish early childhood that included exclusive schools until the age of 13.

However, Margaretha’s father went bankrupt in 1889, her parents divorced soon thereafter, and her mother died in 1891. Her father remarried in Amsterdam on 9 February 1893 to Susanna Catharina ten Hoove (11 March 1844 – 1 December 1913), with whom he had no children. The family had fallen apart and Margaretha moved to live with her godfather, Mr. Visser, in Sneek. In Leiden, she studied to be a kindergarten teacher, but when the headmaster began to flirt with her conspicuously, she was removed from the institution by her offended godfather. After only a few months, she fled to her uncle’s home in The Hague.

Dutch East Indies

At 18, Margaretha answered an advertisement in a Dutch newspaper placed by Dutch Colonial Army Captain Rudolf MacLeod (1 March 1856 – 9 January 1928) who was living in the then Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and was looking for a wife. Margaretha married Rudolf in Amsterdam on 11 July 1895. He was the son of Captain John Brienen MacLeod (a descendant of the Gesto branch of the MacLeods of Skye, hence his Scottish-sounding name) and Dina Louisa, Baroness Sweerts de Landas. This was significant as the marriage enabled her to move into the Dutch upper class and her finances were placed on sound footing. They moved to Malang on the East side of the island of Java and had two children, Norman-John MacLeod (30 January 1897 – 27 June 1899) and Louise Jeanne MacLeod (2 May 1898 – 10 August 1919).

The marriage was an overall disappointment. MacLeod appears to have been an alcoholic who would take out his frustrations on his wife, who was twenty years younger, and whom he blamed for his lack of promotion. He also openly kept a concubine, a socially accepted practice in the Dutch East Indies at that time. The disenchanted Margaretha abandoned him temporarily, moving in with Van Rheedes, another Dutch officer. For months, she studied the Indonesian traditions intensively, joining a local dance company. In 1897, she revealed her artistic name of Mata Hari, Indonesian for "sun" (literally, "eye of the day"), from the Sanskrit "goddess" and "god," via correspondence to her relatives in Holland.

The marriage was an overall disappointment. MacLeod appears to have been an alcoholic who would take out his frustrations on his wife, who was twenty years younger, and whom he blamed for his lack of promotion. He also openly kept a concubine, a socially accepted practice in the Dutch East Indies at that time. The disenchanted Margaretha abandoned him temporarily, moving in with Van Rheedes, another Dutch officer. For months, she studied the Indonesian traditions intensively, joining a local dance company. In 1897, she revealed her artistic name of Mata Hari, Indonesian for "sun" (literally, "eye of the day"), from the Sanskrit "goddess" and "god," via correspondence to her relatives in Holland.

At MacLeod’s urging, Margaretha returned to him, although his aggressive demeanour did not change. She escaped her circumstances by studying the local culture. In 1899, their children fell violently ill from complications relating to the treatment of syphilis contracted from their parents, though the family claimed they were poisoned by an irate servant. Jeanne survived, but Norman died. Some sources maintain that one of Rudolf’s enemies may have poisoned a supper to kill both of their children. After moving back to the Netherlands, Rudolf left her in 1902 and took Jeanne with him. The couple divorced in 1907. Margaretha was awarded custody of Jeanne, but after Rudolf deliberately reneged on a support payment, Margaretha was forced to give Jeanne back to him. Jeanne later died at the age of 21, also possibly from complications relating to syphilis.

Paris  In 1903, Margaretha moved to Paris, where she performed as a circus horse rider, using the name Lady MacLeod, much to the disapproval of the Dutch MacLeods. Struggling to earn a living, she also posed as an artist’s model.

In 1903, Margaretha moved to Paris, where she performed as a circus horse rider, using the name Lady MacLeod, much to the disapproval of the Dutch MacLeods. Struggling to earn a living, she also posed as an artist’s model.

By 1905, Mata Hari began to win fame as an exotic dancer. She was a contemporary of dancers Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, leaders in the early modern dance movement, which around the turn of the 20th century looked to Asia and Egypt for artistic inspiration. Critics would later write about this and other such movements within the context of Orientalism. Gabriel Astruc became her personal booking agent.

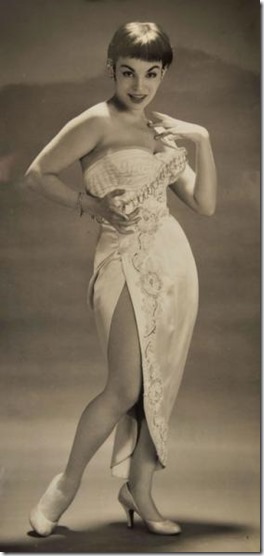

Promiscuous, flirtatious, and openly flaunting her body, Mata Hari captivated her audiences and was an overnight success from the debut of her act at the Musée Guimet on 13 March 1905. She became the long-time mistress of the millionaire Lyon industrialist Émile Étienne Guimet, who had founded the Musée. She posed as a Java princess of priestly Hindu birth, pretending to have been immersed in the art of sacred Indian dance since childhood. She was photographed numerous times during this period, nude or nearly so. Some of these pictures were obtained by MacLeod and strengthened his case in keeping custody of their daughter.

Mata Hari brought this carefree provocative style to the stage in her act, which garnered wide acclaim. The most celebrated segment of her act was her progressive shedding of clothing until she wore just a jeweled bra and some ornaments upon her arms and head. She was seldom seen without a bra, as she was self-conscious about being small-breasted. She wore a bodystocking for her performances that was similar in color to her own skin.

Although Mata Hari’s claims about her origins were fictitious, it was very common for entertainers of her era to invent colorful stories about their origins as part of the show. Her act was spectacularly successful because it elevated exotic dance to a more respectable status, and so broke new ground in a style of entertainment for which Paris was later to become world famous. Her style and her free-willed attitude made her a very popular woman, as did her eagerness to perform in exotic and revealing clothing. She posed for provocative photos and mingled in wealthy circles. At the time, as most Europeans were unfamiliar with the Dutch East Indies and thus thought of Mata Hari as exotic, it was assumed her claims were genuine.

By about 1910, myriad imitators had arisen. Critics began to opine that the success and dazzling features of the popular Mata Hari were due to cheap exhibitionism and lacked artistic merit. Although she continued to schedule important social events throughout Europe, she was held in disdain by serious cultural institutions as a dancer who did not know how to dance.

By about 1910, myriad imitators had arisen. Critics began to opine that the success and dazzling features of the popular Mata Hari were due to cheap exhibitionism and lacked artistic merit. Although she continued to schedule important social events throughout Europe, she was held in disdain by serious cultural institutions as a dancer who did not know how to dance.

Mata Hari’s career went into decline after 1912. On March 13, 1915, she performed in what would be the last show of her career. She had begun her career relatively late for a dancer, and had started putting on weight. However, by this time she had become a successful courtesan, though she was known more for her sensuality and eroticism rather than for striking classical beauty. She had relationships with high-ranking military officers, politicians, and others in influential positions in many countries. Her relationships and liaisons with powerful men frequently took her across international borders. Prior to World War I, she was generally viewed as an artist and a free-spirited bohemian, but as war approached, she began to be seen by some as a wanton and promiscuous woman, and perhaps a dangerous seductress.

"Double agent?"  During World War I, the Netherlands remained neutral. As a Dutch subject, Margaretha Zelle was thus able to cross national borders freely. To avoid the battlefields, she travelled between France and the Netherlands via Spain and Britain, and her movements inevitably attracted attention. In 1916, she was travelling by steamer from Spain when her ship called at the English port of Falmouth. There she was arrested and brought to London where she was interrogated at length by Sir Basil Thomson, Assistant Commissioner at New Scotland Yard in charge of counter-espionage. He gave an account of this in his 1922 book Queer People, saying that she eventually admitted to working for French Intelligence. Initially detained in Cannon Street police station, she was then released and stayed at the Savoy Hotel. A full transcript of the interview is in Britain’s National Archives and was broadcast with Mata Hari played by Eleanor Bron on the independent station London Broadcasting in 1980.

During World War I, the Netherlands remained neutral. As a Dutch subject, Margaretha Zelle was thus able to cross national borders freely. To avoid the battlefields, she travelled between France and the Netherlands via Spain and Britain, and her movements inevitably attracted attention. In 1916, she was travelling by steamer from Spain when her ship called at the English port of Falmouth. There she was arrested and brought to London where she was interrogated at length by Sir Basil Thomson, Assistant Commissioner at New Scotland Yard in charge of counter-espionage. He gave an account of this in his 1922 book Queer People, saying that she eventually admitted to working for French Intelligence. Initially detained in Cannon Street police station, she was then released and stayed at the Savoy Hotel. A full transcript of the interview is in Britain’s National Archives and was broadcast with Mata Hari played by Eleanor Bron on the independent station London Broadcasting in 1980.

It is unclear if she lied on this occasion, believing the story made her sound more intriguing, or if French authorities were using her in such a way, but would not acknowledge her due to the embarrassment and international backlash it could cause.

In January of 1917, the German military attaché in Madrid transmitted radio messages to Berlin describing the helpful activities of a German spy, code-named H-21. French intelligence agents intercepted the messages and, from the information it contained, identified H-21 as Mata Hari. The messages were in a code that some claimed that German intelligence knew had already been broken by the French (in fact it had been broken not by the French, but by the British "Room 40" team), leaving some to claim that the messages were contrived. However, this same code, which the Germans were convinced was unbreakable was used to transmit the Zimmermann Telegram; its unintended interception some weeks later precipitated the United States’s entry into the war against Germany.

Trial and execution

Trial and execution

On 13 February 1917, Mata Hari was arrested in her room at the Hotel Elysée Palace, on the Champs Elysée, where HSBC later established its French headquarters, in Paris. She was put on trial on 24 July, accused of spying for Germany, and consequently causing the deaths of at least 50,000 soldiers. Although the French and British intelligence suspected her of spying for Germany, neither could produce definite evidence against her. Secret ink was found in her room, which was incriminating evidence in that period. She contended that it was part of her make-up. She wrote several letters to the Dutch Consul in Paris, claiming her innocence. "My international connections are due of my work as a dancer, nothing else …. Because I really did not spy, it is terrible that I cannot defend myself." Her defense attorney, veteran international lawyer Edouard Clunet, faced impossible odds; he was denied permission either to cross-examine the prosecution’s witnesses or to examine his own witnesses directly. Under the circumstances, her conviction was a foregone conclusion. She was executed by firing squad on 15 October 1917, at the age of 41.

German documents unsealed in the 1970s proved that Mata Hari was truly a German agent.[citation needed] In the autumn of 1915, she entered German service, and on orders of section III B-Chief Walter Nicolai, she was instructed about her duties by Major Roepell during a stay in Cologne. Her reports were to be sent to the Kriegsnachrichtenstelle West (War News Post West) in Düsseldorf under Roepell as well as to the Agent mission in the German embassy in Madrid under Major Arnold Kalle, with her direct handler being Captain Hoffmann, who also gave her the code name H-21.

In December of 1916, the French Second Bureau of the French War Ministry let Mata Hari obtain the names of six Belgian agents. Five were suspected of submitting fake material and working for the Germans, while the sixth was suspected to be a double agent for Germany and France. Two weeks after Mata Hari had left Paris for a trip to Madrid, the double agent was executed by the Germans, while the five others continued their operations. This development served as proof to the Second Bureau that the names of the six spies had been communicated by Mata Hari to the Germans.

Disappearance and rumours

Mata Hari’s body was not claimed by any family members and was accordingly used for medical study. Her head was embalmed and kept in the Museum of Anatomy in Paris, but in 2000, archivists discovered that the head had disappeared, possibly as early as 1954, when the museum had been relocated.[citation needed] Records dated from 1918 show that the museum also received the rest of the body, but none of the remains could later be accounted for.

A 1934 New Yorker article reported that at her execution she wore "a neat Amazonian tailored suit, especially made for the occasion, and a pair of new white gloves" though another account indicates she wore the same suit, low-cut blouse and tricorn hat ensemble which had been picked out by her accusers for her to wear at trial, and which was still the only full, clean outfit which she had along in prison. Neither description matches photographic evidence. According to an eyewitness account by British reporter Henry Wales, she was not bound and refused a blindfold. Wales records her death, saying that after the volley of shots rang out, "Slowly, inertly, she settled to her knees, her head up always, and without the slightest change of expression on her face. For the fraction of a second it seemed she tottered there, on her knees, gazing directly at those who had taken her life. Then she fell backward, bending at the waist, with her legs doubled up beneath her." A non-commissioned officer then walked up to her body, pulled out his revolver, and shot her in the head to make sure she was dead.

Text from Wikipedia